Reverse engineering… Could it be just the opposite of engineering? Is it that simple? Let’s see!

Reverse engineering is a very broad field which has lots of applications. Not just that, but almost anything can be reverse engineered too. Let’s take a look at it in this post.

Reverse Engineering

Reverse engineering is basically understanding the internals of something without having access to the original design. While a lot of people think of software when the words “reverse engineering” are said, it, unsurprisingly, isn’t limited to software.

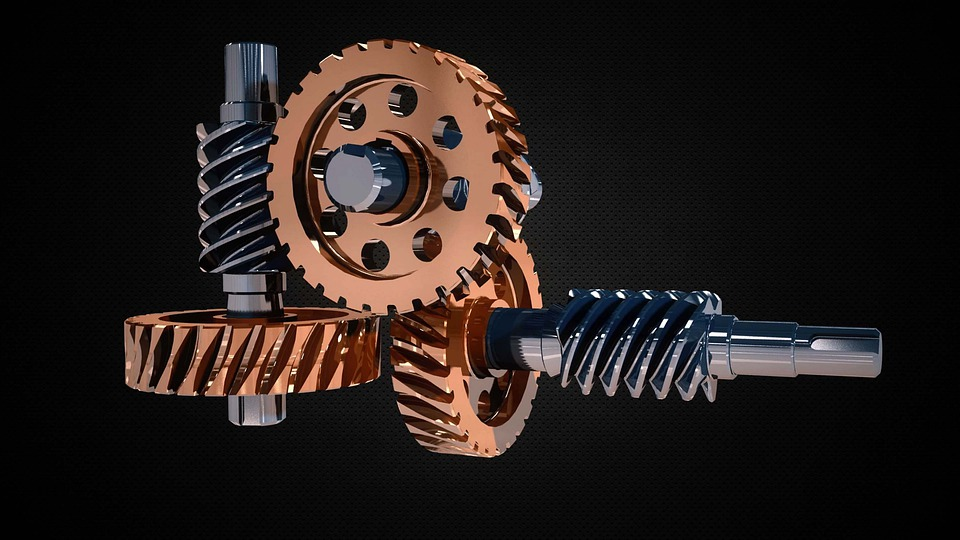

Anything that has properties and behaviour can be reverse engineered. For example, mechanical parts can be reverse engineered to create a replacement for a broken part in a mechanical system if a replacement is no longer being sold. You would have to reverse engineer the system, know where that part fits, what its dimensions are, what material it is made of, etc…

Anything, you say? Well, yes. Maybe you could even figure out how to make a Nuka-Cola… Easy on the radiation, though!

Electronics Reverse Engineering

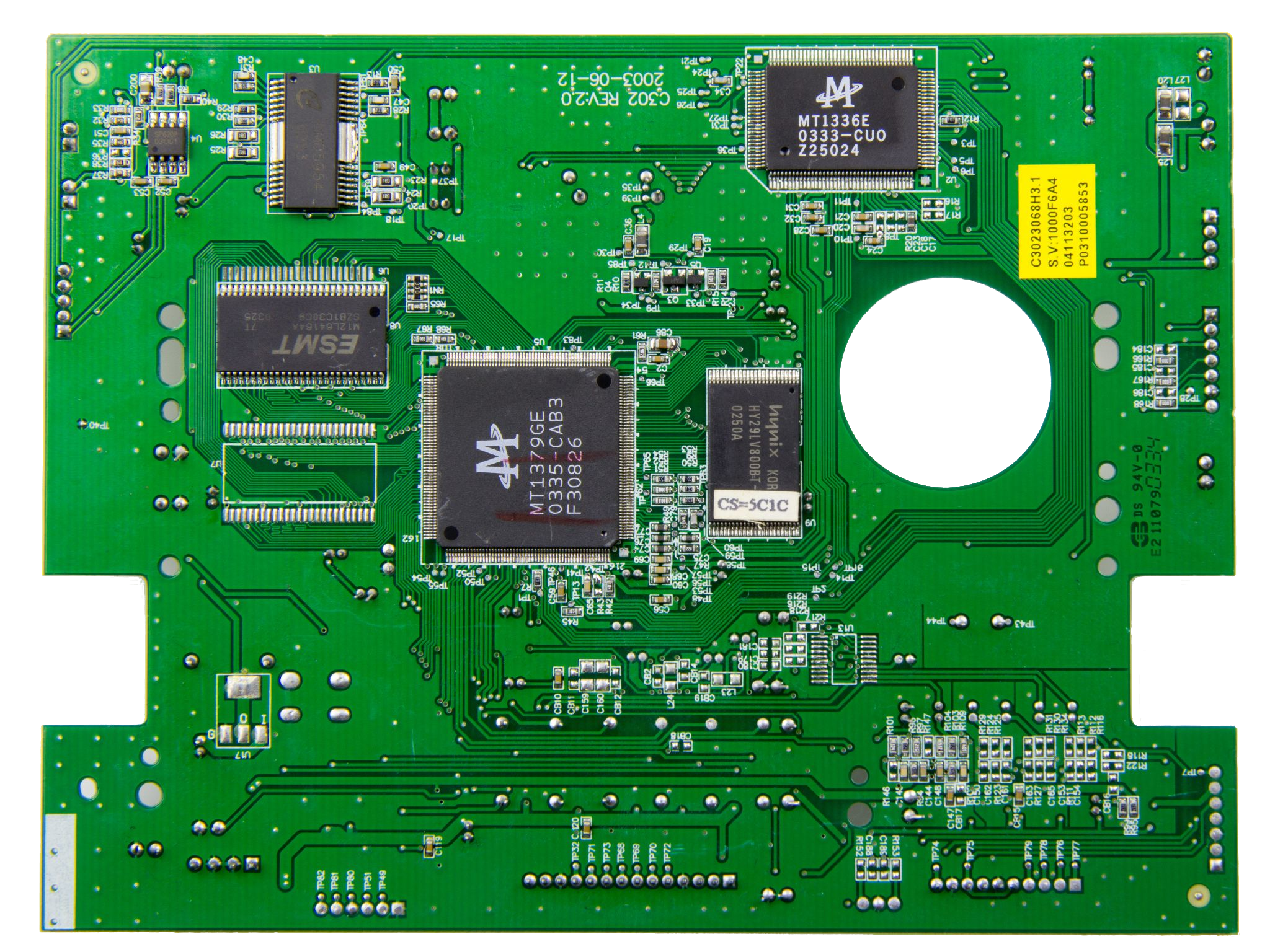

Modern electronic circuit boards are usually complex and have a lot of components. Just by looking at a PCB, you wouldn’t really know what it does most of the time. However, you can start following the traces, chips, and other components on the PCB and figure out exactly what it consists of and how they’re connected. Add some more specialised tools, some reverse engineering skills, and you now know how the logic inside the circuit itself (or even the chips themselves) works.

Software Reverse Engineering

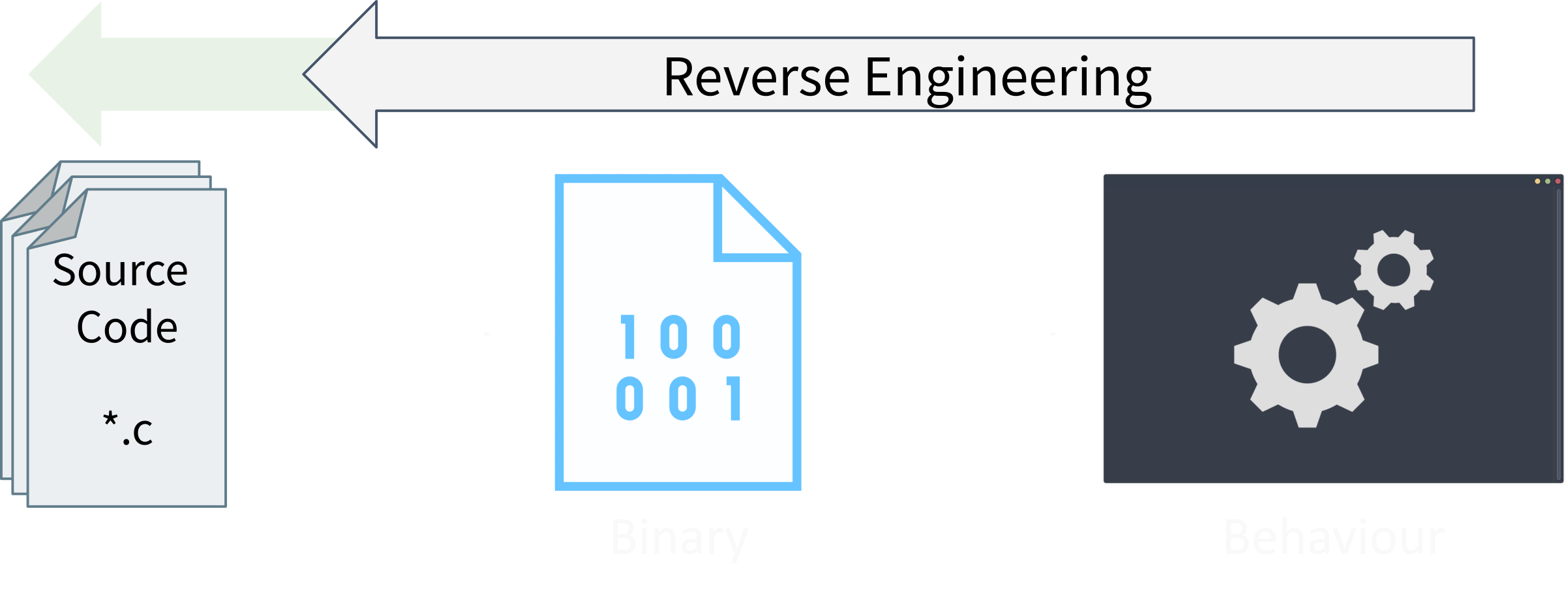

Like all other forms of reverse engineering, software reverse engineering is understanding how software works without having access to its original design.

In this case, the design/implementation is the source code. You can check The Life of a Binary to understand more on how software is built. But the summary is as follows:

- Software is compiled from source code into a binary file (also known as a program)

- The binary file is loaded by the operating system

- The program behaves based on how it is programmed

- e.g. You click some button you get some action

We can do exactly the opposite of that and then we would’ve reverse engineered a program. With only one difference: we don’t go back to the original source code. We only want to understand how the program is behaving. We can’t get the exact original source code from the binary, and luckily, that doesn’t matter! It doesn’t matter what a variable’s name is or how a developer decided to write a function. As long as we have a behaviour, we can reverse engineer it and we can get pretty close to what the developer wrote. Just not the exact same source code.

To explain this a bit further, you will understand what the binary is doing and what its internals are. But, you will never be able to know what the actual code the developer wrote was. Which, again, doesn’t matter. You know what the program does and how it does it. That’s the goal of reverse engineering.

We will get to know more about how reversing is done and what will be looking at to do so when we talk about disassemblers and decompilers later on in this post!

For now, let’s see how any of this is useful.

Applications of Reverse Engineering

Reverse Engineering has many uses. Here are some of them!

Exploit and Malware Development

To develop malware and exploits for a specific platform, you may need to reverse engineer parts of it to understand how it works. In this case, it is particularly useful if you’re doing a black box penetration test where you don’t know much about the platform before-hand.

Exploit/Malware Analysis

Malware is literally just malicious software, software that does bad things. Therefore, malware analysis can be seen as “just” reverse engineering such bad software. Of course, it is more complicated than that. But, we can stick to that abstraction for now. :)

Cyber Espionage

How do you best understand the capabilities of your enemy? Get hold of it and take it apart. Militaries do so with aircraft and tanks, and cyber weapons are no exception.

Hardware and Low Level Security

Lower level software and firmware are often more locked down and complex. A lot of the time, a researcher would have to reverse engineer a certain part of whichever platform their researching due to it being undocumented, for example.

Interfacing and Electronic Component Obsolescence

When you want to interface two electronic components, you may have to reverse engineer one of them (or both) to find out how it works and what would be the suitable way to connect it to the other components. This also helps when an old component becomes obsolete and you want to replace it with a newer component but there isn’t documentation on how they work together.

Deep Dive: Software Reverse Engineering

At this point, I really recommend that you go and read The Life of a Binary if you haven’t. Anyway, the end product of the building process of software leads to having a program which behaves in a certain way. This program is actually more or less just machine code (AKA 0s and 1s) telling the CPU what to do. Sure, there are other elements to it, which we discuss in the other blog post mentioned. The summary is, we have a program which is basically a file of machine code and we want to reverse engineer it.

How can we do so?

Disassemblers

To put it simply, a disassembler does the opposite of what an assembler does. It parses the machine code and displays it in human-readable assembly. Or at least, that’s what a basic disassembler would do. Modern disassemblers often add features like symbol resolution, API call parameter highlighting, and a couple of other neat features that may help you.

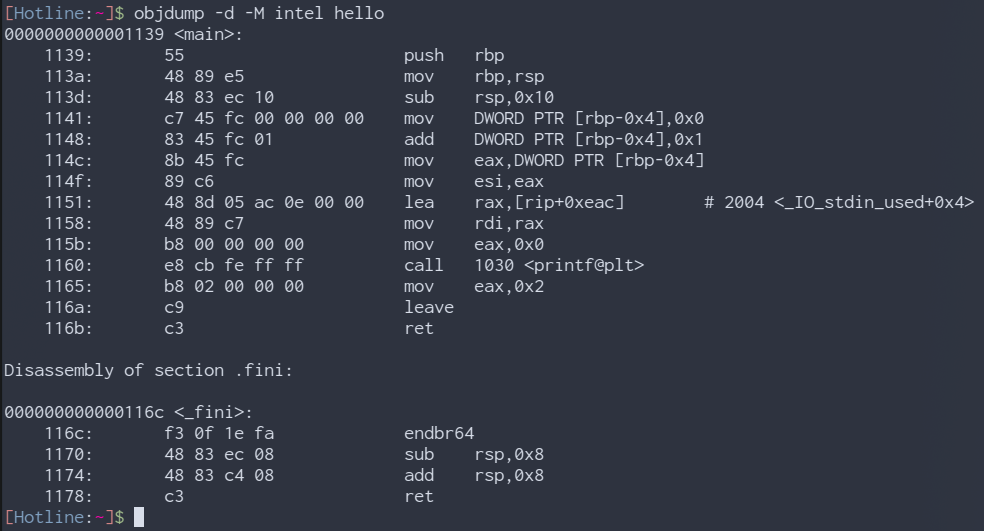

objdump (part of GNU Binutils v2.41.0), a command line utility which has disassembly features

Disassemblers are generally used to get to the deepest details of what a binary does. As it shows you all the assembly instructions and there usually won’t be anything beyond that except API calls which can be looked up in their documentation a lot of the time.

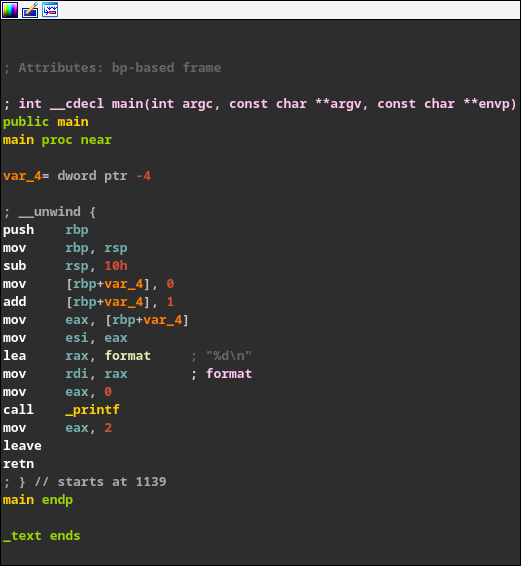

IDA Free 8.3, a very powerful disassembler and debugger. Also a bit of a nicer tool to use compared to objdump

Some malware and sometimes legitimate software try to trick disassemblers into displaying the wrong assembly code by exploiting the way they work. Anti-disassembly is a very interesting topic which you may want to read about.

Debuggers

Debuggers, well, help you debug. Wouldn’t have guessed it, would you? Jokes aside, debuggers can be used to run a program instruction-by-instruction and see what is actually happening. Just like any debugger you’ve used before, they have breakpoints, step into, step over, step out, etc… Very useful.

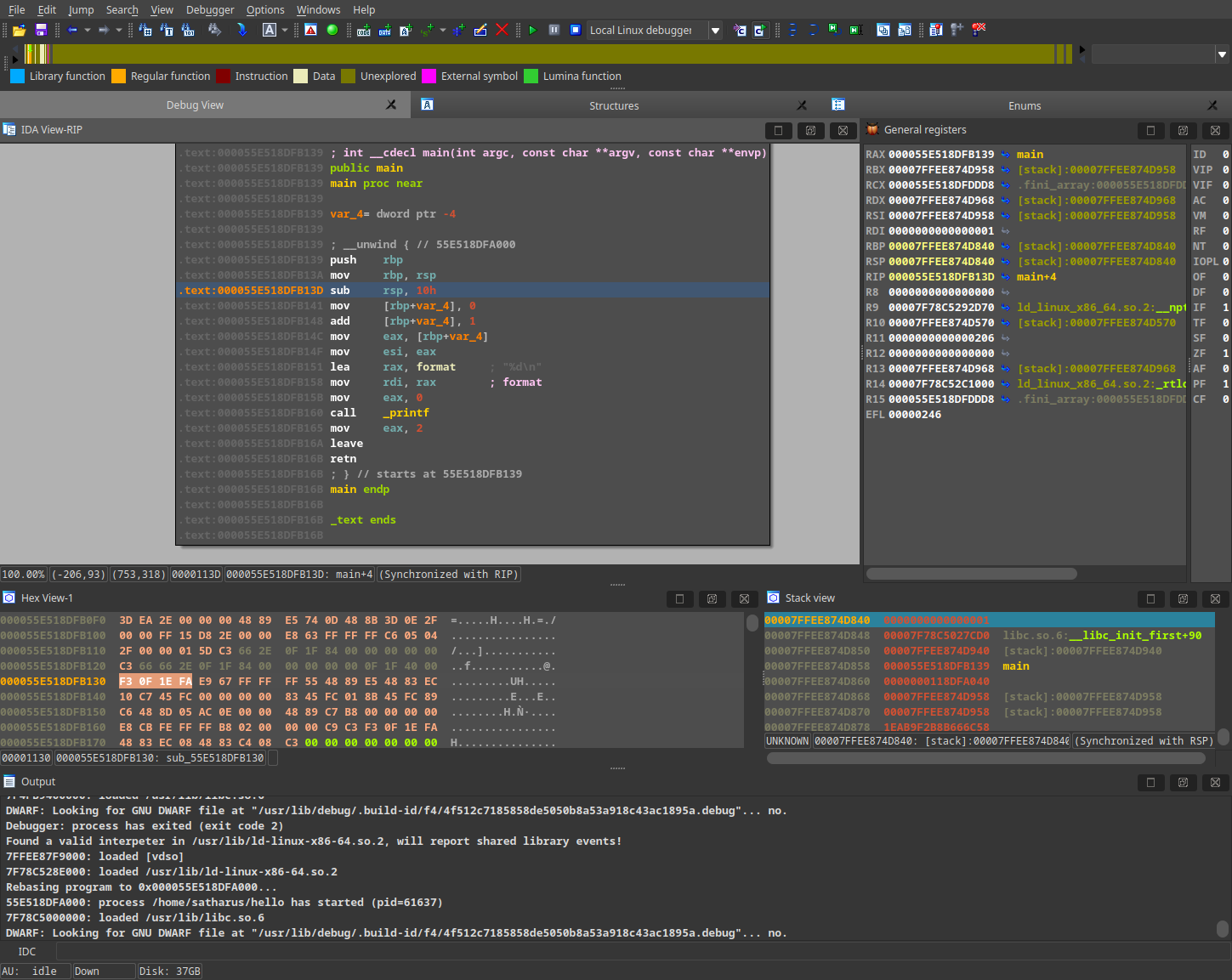

IDA Free 8.3 debugging a binary

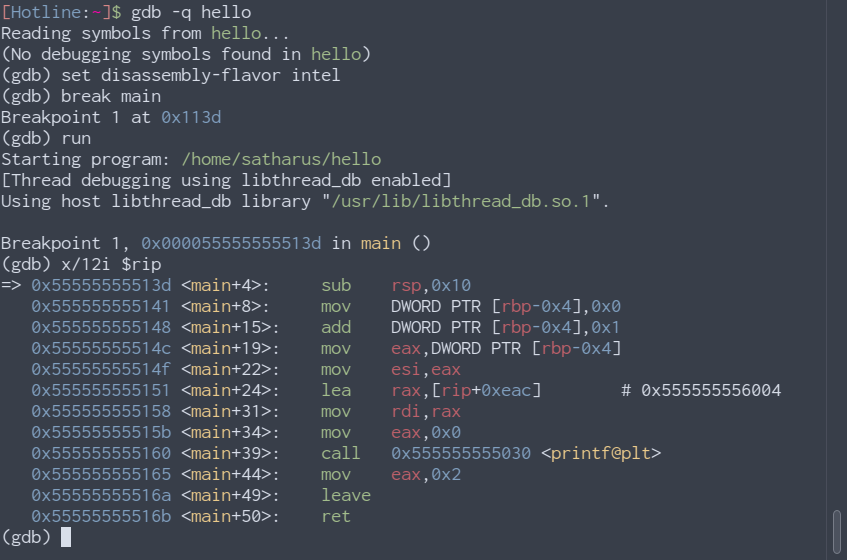

gdb, a powerful command line-based debugger

Decompilers

A decompiler, like you may have already guessed, shows you the program in a pseudo-code-like format. It presents the file in an arguably more readable format which is sometimes easier to understand but also not always accurate. The decompiler tries to interpret and guess what the assembly it sees was as code before it got compiled. It won’t always work 100% accurately. However, it is very useful sometimes to understand blocks of assembly that may get a bit confusing.

IDA Free 8.3 Cloud-based Decompiler

Just because these exist, doesn’t mean you don’t need to learn assembly. You will need assembly.

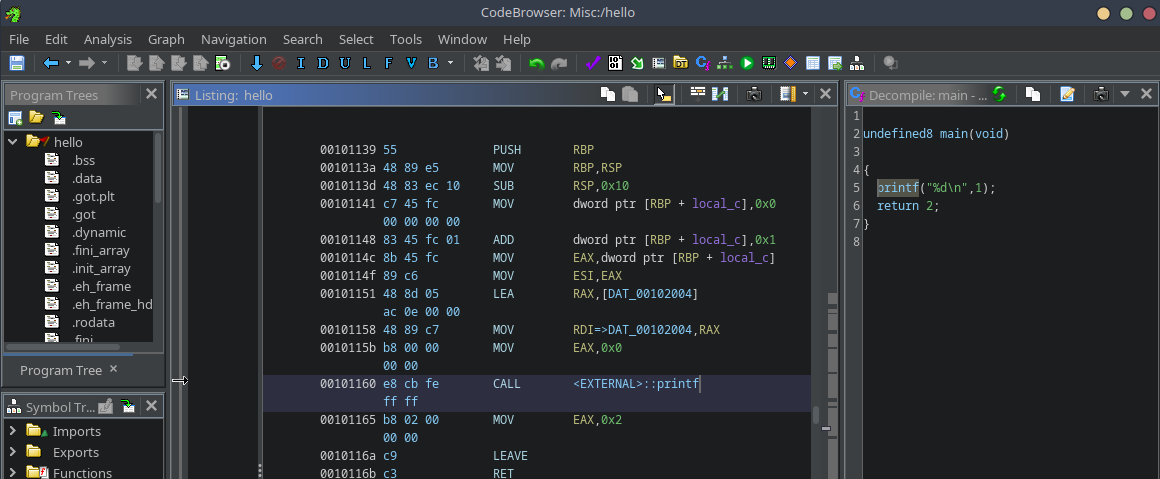

Ghidra 10.3, a very powerful decompiler and disassembler, with a recently added debugger

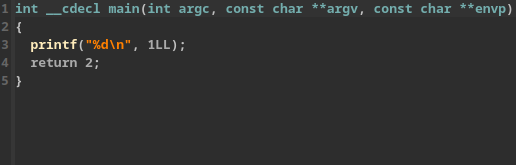

Notice here how both decompilers show printf("%d\n", 1); even though that isn’t what is exactly happening in the assembly. I can also assure you that it isn’t what I wrote for this example binary!

The original code I wrote was:

int x = 0;

x++;

printf("%d\n", x);

While both the decompiled code and the one I wrote present the same output, they’re not exactly the same. I am not saying that decompilers are entirely inaccurate, just be mindful that they’re not entirely accurate either.

Intermediate Language

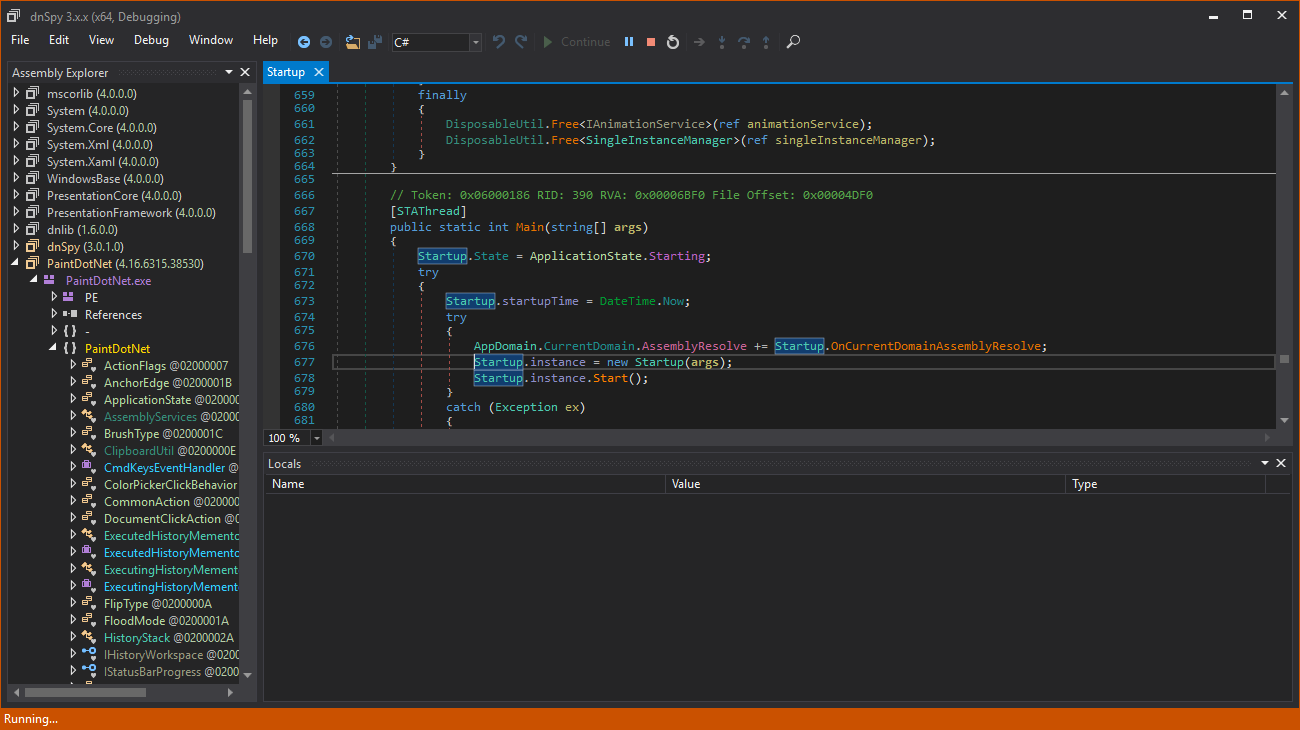

Some languages, aren’t compiled directly to machine code. They are, instead, compiled to some form of intermediate language which is then compiled at runtime into machine code. These languages are much easier to decompile and usually don’t require an understanding of actual machine code. Example languages are Java and C#, they are both compiled at runtime by a VM such as JRE or the .NET CLR.

dnSpy, a .NET decompiler and debugger

Notice how in dnSpy, there is no assembly to read or anything. You get a decompiled version of the original code which could be pretty similar to the original.

Other Useful Tools

Some other tools can be useful to find out information about binaries you want to reverse. Some examples:

- Explorer Suite: A complete suite of Windows binary utilities

- GNU Binutils: A suit of utilities for Linux binaries. Contains the popular tool strings which can be used to find readable strings in binaries, as well as objdump

- Analysers, such as:

- Hex Editors: Have multiple uses including modifying existing binaries if needed, extracting data from them, etc…

Ethics of Reverse Engineering

You legally and ethically aren’t allowed to reverse engineer everything in the world. The reason why you’re reversing something also matters a lot. For example, reversing commercial software is often restricted. But, reversing malware, open sample code, and open source software is fine for the most part.

Make sure to check which regulations apply in your region of residence AND region of work and obviously make sure you follow them! You can also check out the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Reverse Engineering FAQs for a US perspective on this.

I am not a lawyer, don’t take anything I say here as any form of legal advice.

Great, Where do I Learn More?

Well, depends on what kind of reverse engineering you want to do.

Personally, I would generally recommend the following if you want to go for software reverse engineering:

- Brush up on your C knowledge

- Understanding pointers and data structures is usually enough

- Learn x86 Assembly

- Learn Reverse Engineering and PRACTICE reversing binaries

- Learn more about binary file structures

- PE Files, ELF Files, Mach-O, etc…

- Learn more advanced x86 and OS-related topics (go as deep as you like)

- Segmentation, paging, operation modes, control registers, SMM

Or don’t… Do whatever makes you good at what you want to do! There is No Single Roadmap.

Needless to say, it doesn’t have to be in this exact order, as long as you cover the basics (the first 4 points)!

You may also want to check OpenSecurityTraining2’s learning paths, depending on what you want to do on the long run.

Some Resources

- Open Security Training 2:

- Open Security Training:

- Other Great Resources:

That’s about it, thanks for reading! I hope you learned something new from this post. If you did, or you at least enjoyed it (or both), please share it with your friends who enjoy staring at hex bytes and assembly code for hours upon end.

Some icon and image credits: WikiMedia Commons, Flaticon, Pixabay, The Noun Project, Pixel perfect