Programs… Binaries… PE Files… ELF Files… What are those? If you’ve read about computers at some point or even just used them, you’ve probably come across these terms. Today we’ll take a look on how programs are built and the stages they go through. This post is a bit of a primer on knowledge required for multiple fields of software engineering and computer science. One of which is software reverse engineering, which I’ll talk about in the next post.

Refresher: Trip to the Computer Class

If you remember, back in primary school you were probably taught something like this:

We use input devices such as a mouse and keyboard to make the computer process whatever we want and then the computer would give us some sort of output such as something visual on a monitor or a sound.

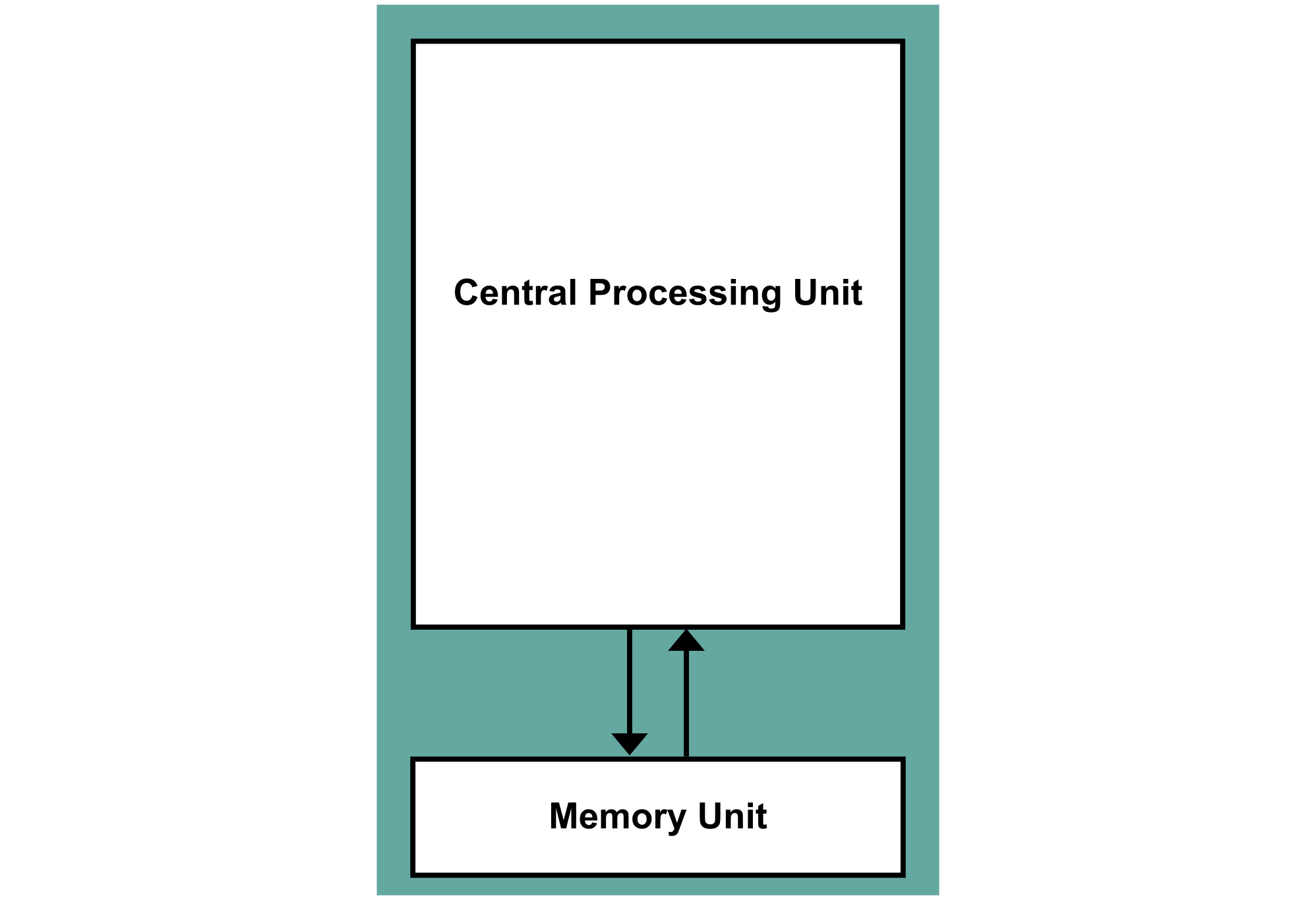

Then, at some point you may have been taught this in university/college if you studied CS or CE.

We give our computer input and get output. What happens in the middle, though?

A quick summary so that you can follow the upcoming parts, the processor (Central Processing Unit) executes instructions given to it by the user. The processor also uses memory to store data it needs during the execution of the instructions mentioned before.

e.g. The OS loads the program you just double clicked into memory, and the processor starts executing the instructions in that program.

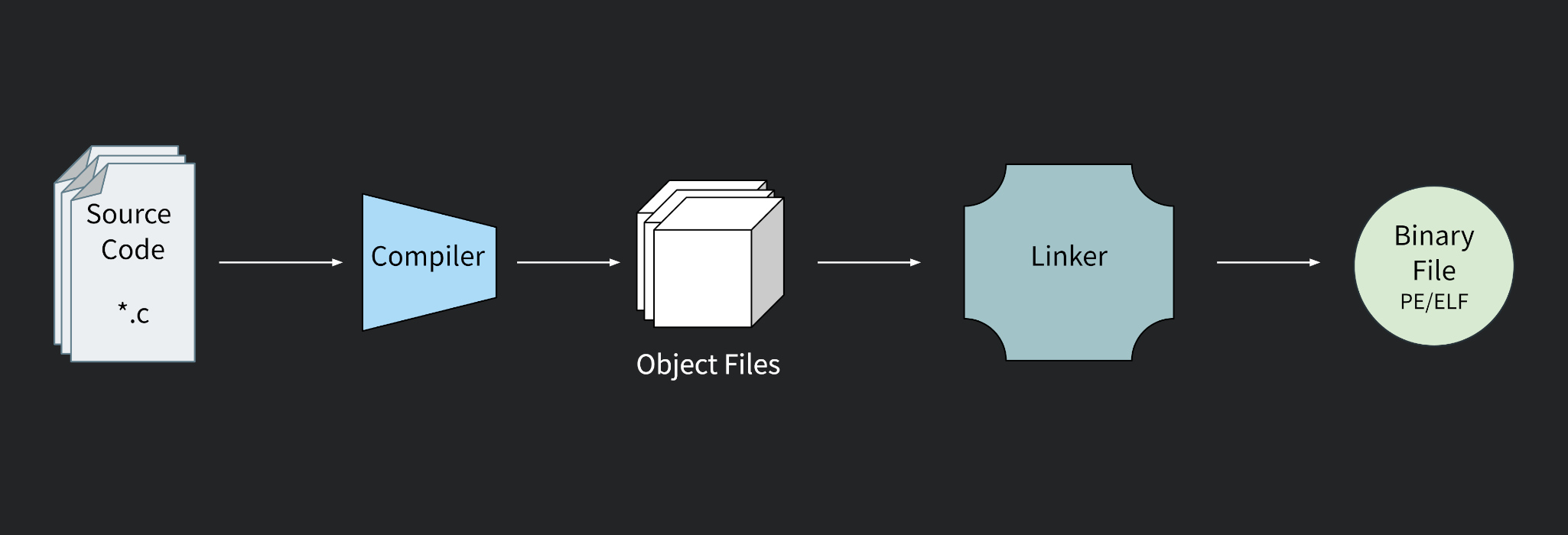

The Birth of a Binary

As mentioned a couple of times previously on this blog, computer programs are written in code. Programming languages such as C, C++, etc… This code is referred to as “Source Code”, as it is the source from which the programs are born.

A PE file is a Portable Executable, a Windows format. Usually seen with extensions .exe, .dll, etc… ELF is the Executable and Linkable Format on Linux. Usually seen without an extension or .so, .o, etc..

The Compiler

The source code files are passed to a compiler, which compiles the high-level human-written code into machine code. Instructions which can be executed by the CPU. Your CPU can’t execute x++ but it can execute inc eax, for example. What a compiler does is basically that. The result of the output from a compiler is an object file. A file containing machine code.

The Linker

When developers write code, they often use libraries which are basically code that has been written by someone else before for a specific purpose and then other developers can just reuse it in their code. Libraries contain functions, and functions are referenced in code by developers. For example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

The above program prints “Hello, world!”. However, you don’t see a definition for printf() in my code. That is because I included stdio.h, the standard C library for input and output (I/O). This tells the compiler to include that library where the function definition lies. The compiler would then have to link the program to that library in order for it to work!

This is where the linker comes in. The linker sees which references from other library the binary needs, and it links the binary to them. i.e. It tells the binary where the function is in the library, and it writes information in the binary for the OS to know that this program needs this library.

But, how does the OS load this program and make it work?

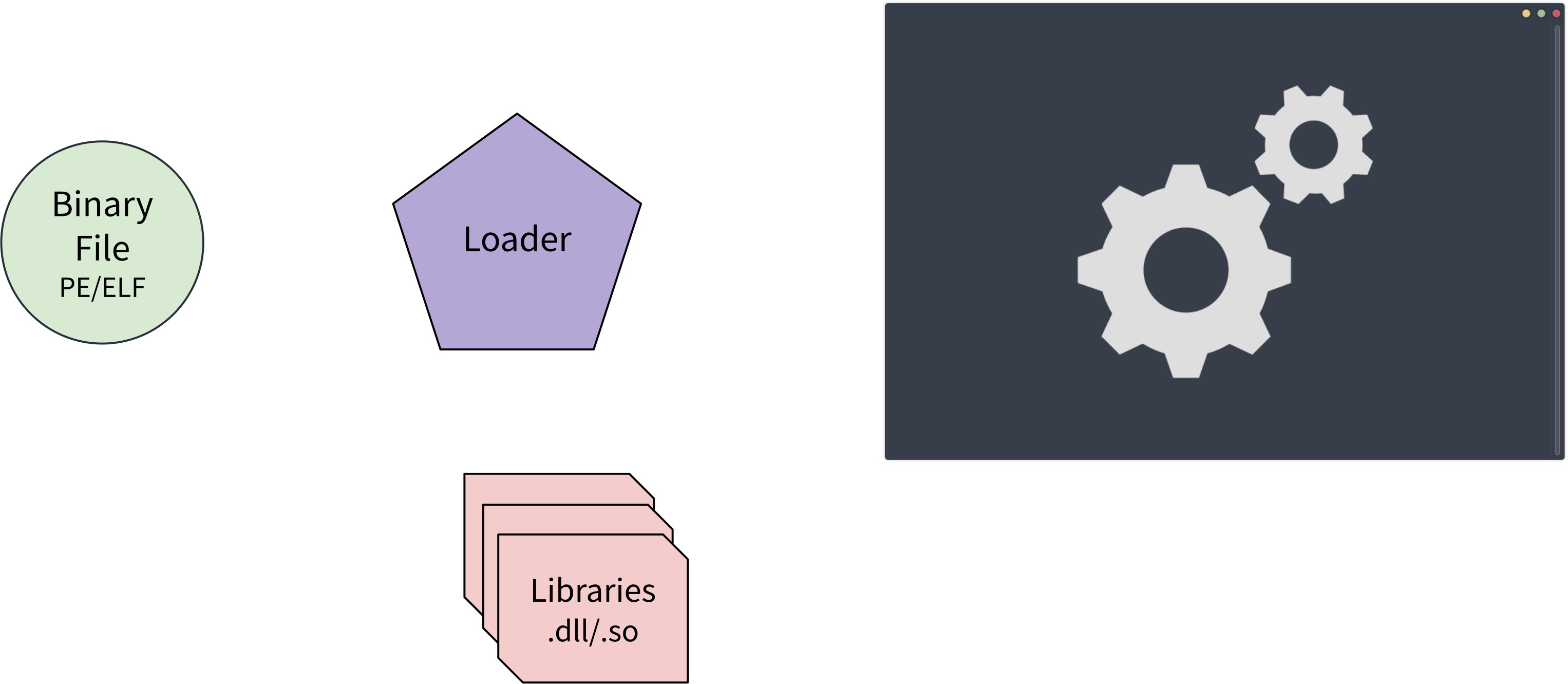

The Life of a Binary

The OS reads the file, loads the content of it where it is appropriate for it to execute, and loads any libraries needed by the binary. Libraries, after all, are just programs. The only difference is that you can’t double click and run them like normal programs.

This is a very simple abstraction, but if I go into how programs are loaded and the actual structures of binary files, this post will be way too long and you will probably click off now. So, let’s talk about it some other day over a cup of tea. For now, check the link to a course at the end of this post to get an idea on where you can learn more.

That way, your program is now running and it has a process id (PID). What started as some Lines of Code (LoC) is now a running program with an id. Gosh, they grow up so quickly  .

.

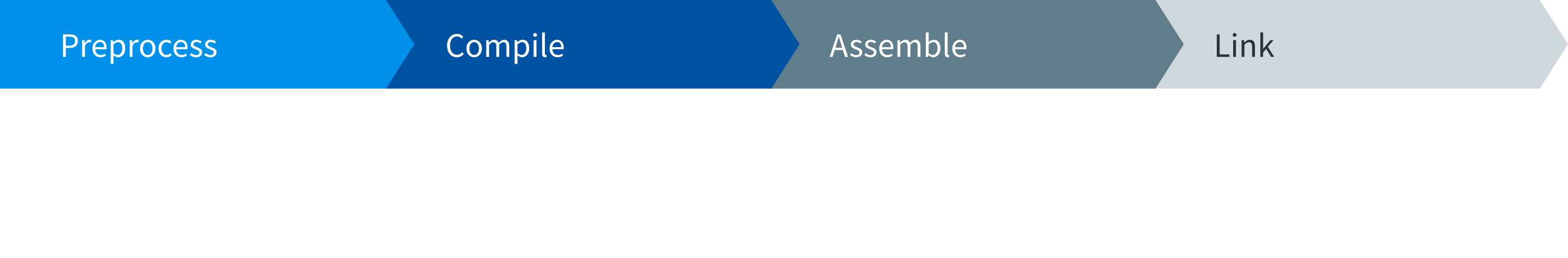

The Compilation Process

Let’s take a bit of a deeper look on the whole process. We now have a high level understanding of how lines of code become a running program. Let’s take a look under the hood and see the four stages of what a modern compiler like gcc for example would do.

This is some C code.

#include <stdio.h>

#define RETURN_VALUE 2

int main()

{

int x = 0;

x++;

printf("%d\n", x);

return RETURN_VALUE;

}

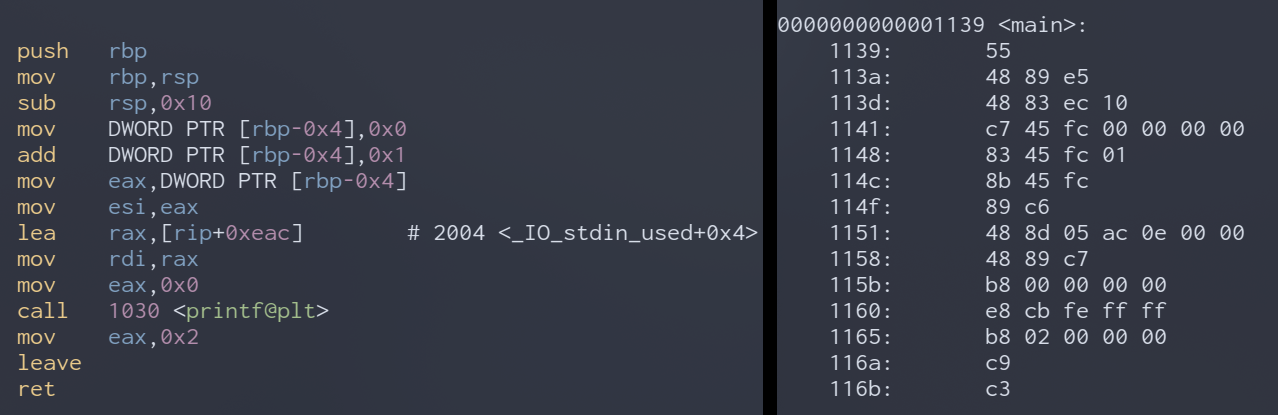

When compiled, it is compiled to the assembly on the left here.

After it is assembled, it’ll look like the machine code (in hex) on the right.

The assembly is for demonstration only. Actual compiled code would look slightly different as it would not yet be linked. However, this code IS linked.

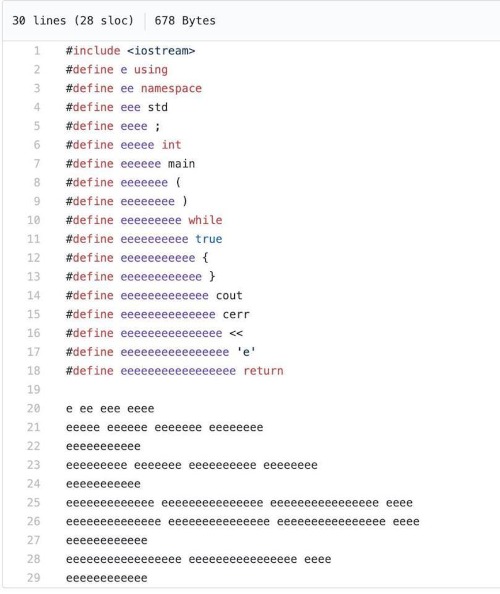

Preprocessing

The preprocessor is a component of the compiler and it processes header files, macro expansions, conditional compilations, etc… For example, before preprocessing we can have a macro like this in our code:

#define SIZE 2*1024 //Macro here

int main()

{

printf("%d", SIZE);

}

After preprocessing, SIZE is replaced with its defined expansion:

int main()

{

printf("%d", 2*1024);

}

The existence of the preprocessor allows us to write code that may be more understandable and easier to change later. Don’t quote me on that, though. As different people have decided that macros should be used in different ways.

I think it is fine, as long as your code doesn’t look like this.

Compilation

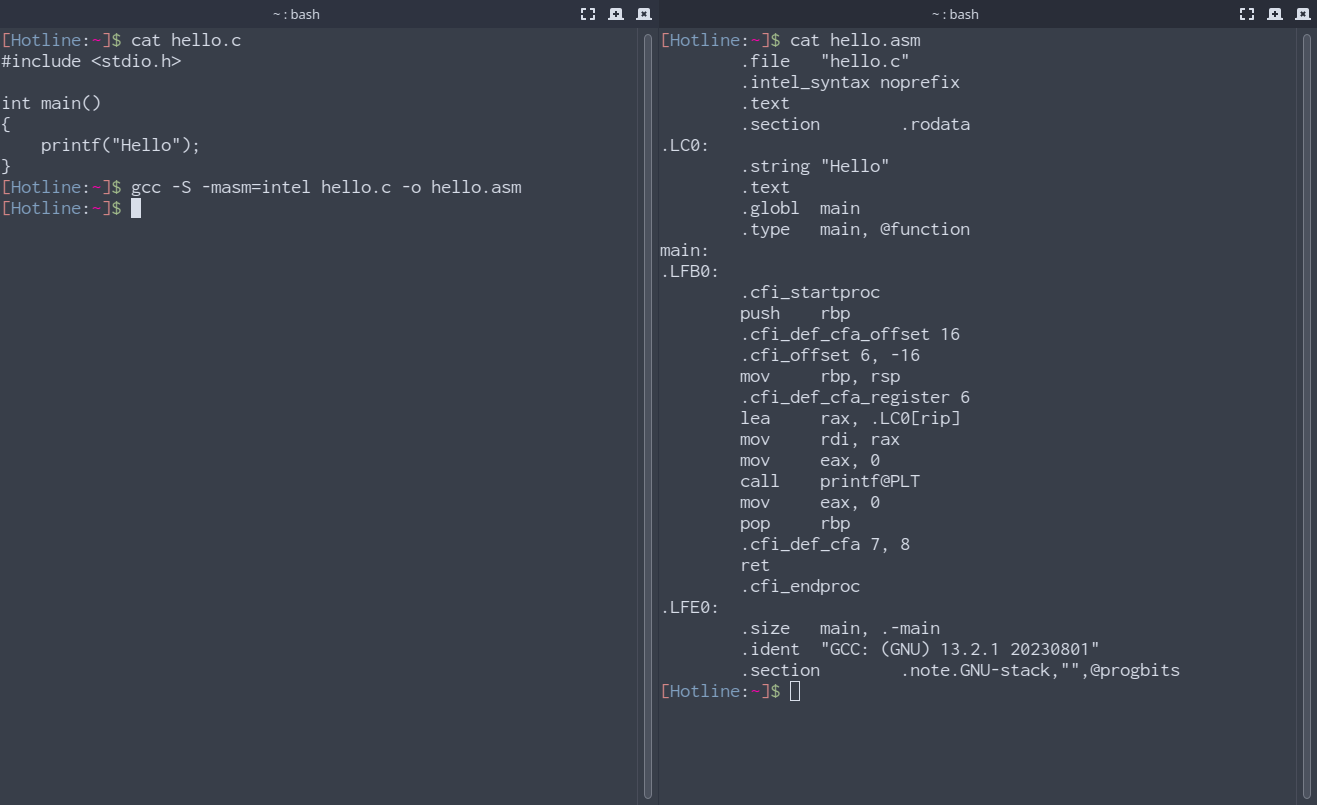

The compilation process is taking the code produced by the preprocessor and compiling it into assmebly. You can run gcc -S -masm=intel and that will preprocess and compile your file only without assembling or linking it. This will show you how the assembly looks.

This file on the right (hello.asm, the output of gcc) is purely human-readable assembly.

Assembly

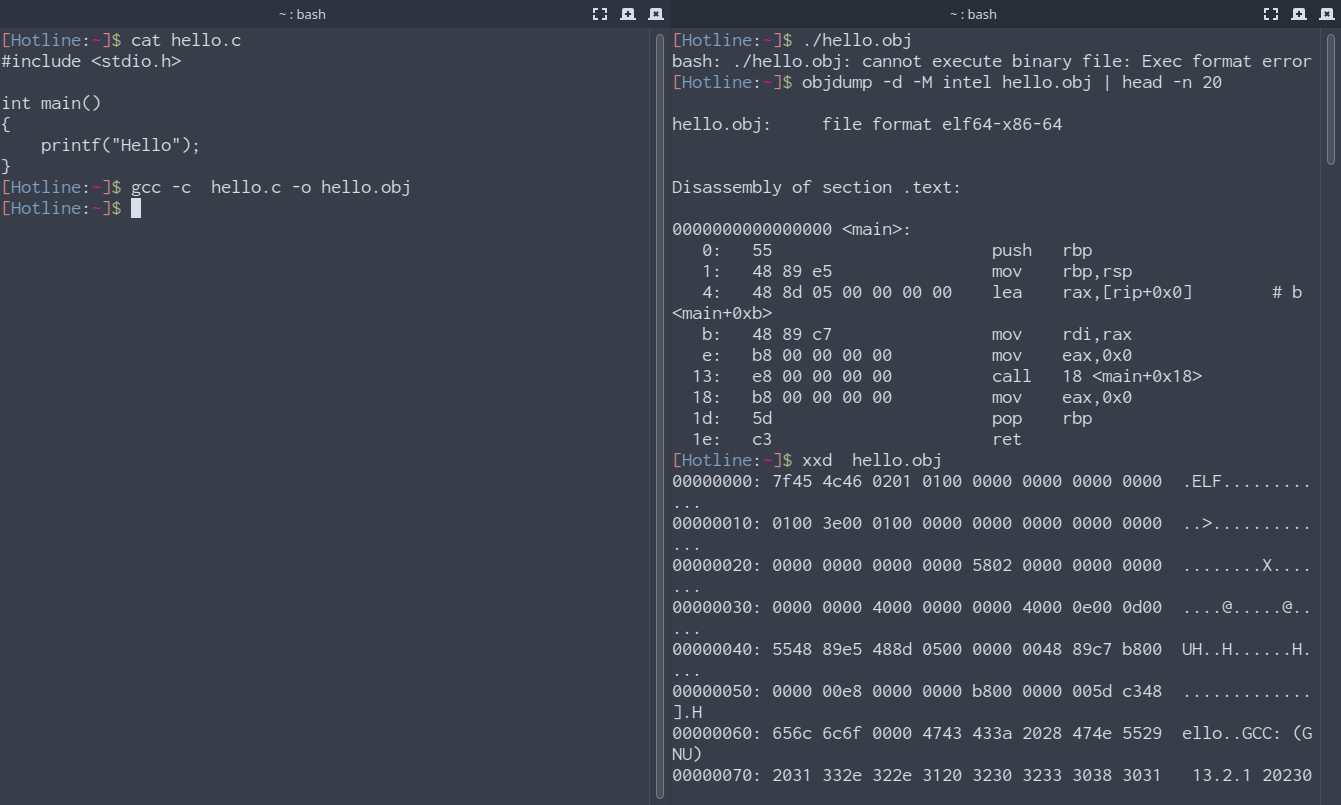

The assembly process assembles the human-readable assembly code into a machine code binary. That binary still isn’t executable as it hasn’t been linked yet. However, it will contain very similar assembly instructions. You can run gcc -c which will preprocess, compile, and assemble the code only. No linking yet.

Notice how, on the right, the file is not executable, and to read it in a human readable format, you need to use special software known as a disassembler (check the next blog post).

Note that during compilation, one line of code could be one instruction or multiple instructions when compiled to assembly. But, when the assembly is converted into machine code, it is mapped one-to-one where each assembly instruction is represented in its machine code format. tl;dr: Assembly is the human readable form of machine code.

| C Code | Assembly | Machine Code |

|---|---|---|

x++ |

inc eax |

0100 0001 |

I know that incrementing a variable x won’t necessarily increment the register eax, please don’t @me… This is a simplification.

Linking

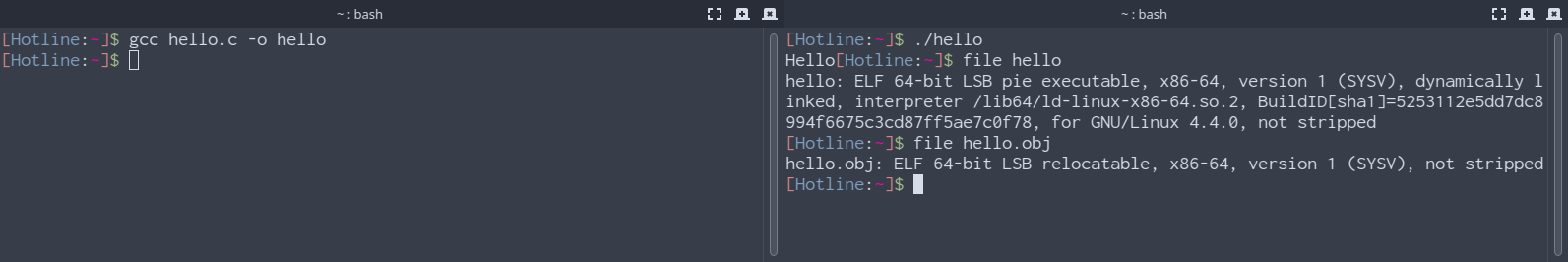

The linker does the last step of the process. It links the binary file to the libraries it needs in order to run. You can run gcc without any flags and it will preprocess, compile, assemble, and link.

Note that on the right, the program is now executable and prints “Hello” as expected. It is also now a “dynamically linked” executable as shown when running the file command.

Notice how that compares to the file hello.obj from the previous stage, which doesn’t state that it is linked.

And that is it. That’s how a binary is born, lives a hopefully fulfilling life, and then is killed by a user because they decided to try a shiny red button with an X on it…

Let’s all come together for computer process rights and stop killing them when they do something as simple as freezing :(

Thanks for reading! If you want to know more about binaries, their structures, and get into this topic in much more detail, please do check out The Life of Binaries. It is an outstanding free course, and -obviously- inspired this blog post.

I hope you enjoyed this post and learned something new! If you did, please share it with your friends who think of the threads and decide to save process’ lives by using SIGTERM instead of SIGKILL.

Some icon and image credits: WikiMedia Commons, Flaticon, The Noun Project