Arab Security Cyber Wargames Finals 2020 was held on September 12th in Nile Ritz Cairo.

Photo Credit: Arab Security Conference.

This time I was the author of three of the five challenges presented in the finals. Here are the writeups for them.

Challenge 1 - EZ

Challenge Difficulty: Easy

Challenge Link: Drive

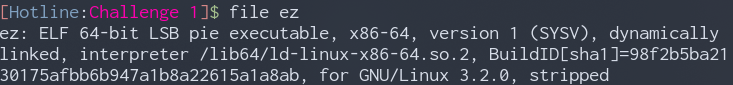

We are presented with a Linux 64-bit stripped executable called ez.

Running the file prints nothing useful. Let’s take a look at in IDA.

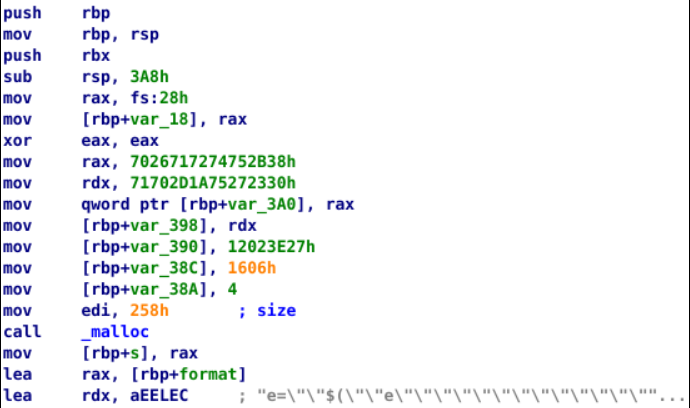

The first few instructions look like this. The values being moved into rax, rdx, and the places after them are interesting we can get back to them later. but for now there seems to be a huge string being loaded into rdx. let’s take a look at it using strings to get it in clean ASCII.

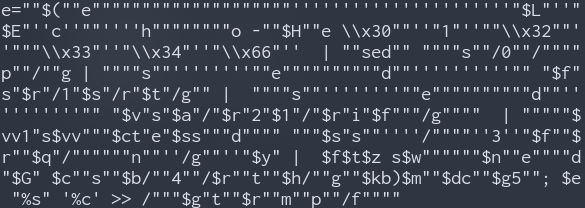

It looks like some obfuscated shell code or something of that sort. Especially that we can see a lot of $ signs, pipes, and the command “sed”.

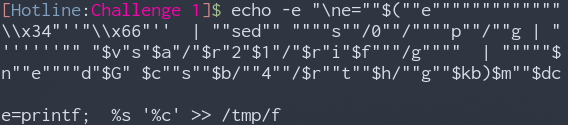

Let’s try and echo that from BASH to try and de-obfuscate it and see what it will produce.

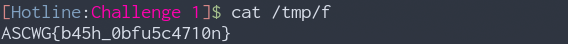

It seems like it is printing something to /tmp/f, let’s try and cat it.

Well there we go 😃 no actual reversing needed.

Flag: ASCWG{b45h_0bfu5c4710n}

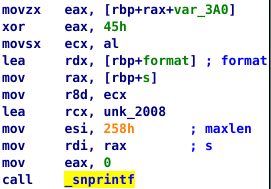

Bonus: Getting the Flag from the Binary itself

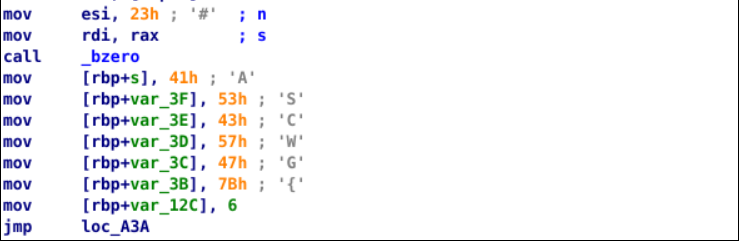

Remember the bytes being moved into memory at the beginning of the program? That’s the XORd flag. We can take the bytes to a python shell and do the magic there.

Challenge 2 - easy-101

Challenge Difficulty: Easy

Challenge Link: Drive

This challenge was written by Eng. Mohammad Khreesha, not me.

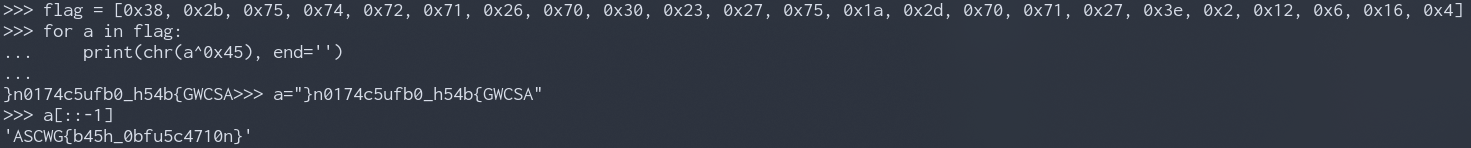

We are presented with a Linux 64-bit executable called easy-101.

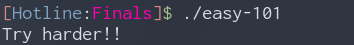

Running it tells us to “Try harder!!”, okay then.

After spamming a couple of different arguments, it kept printing “drink water!!”. the output in ltrace and strace didn’t seem to differ too. So let’s open it up in IDA.

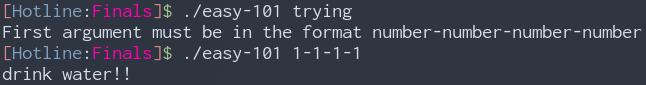

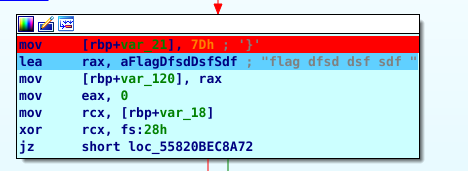

On opening the binary in IDA, we can see that all it does is validate that you have some form of input that has 3 dashes ‘-‘ and then continues to the same block with the big arrays every time.

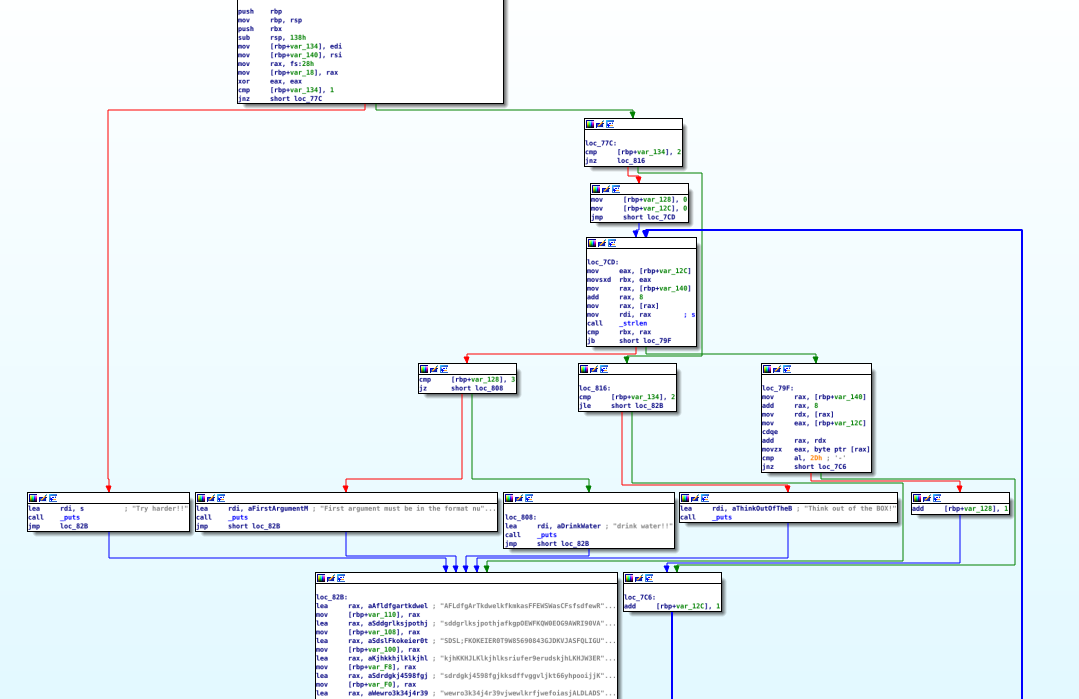

In that same block, we can find that it starts adding the flag format.

We can set a breakpoint at the part when the closing brace is added.

After that, we can click on var_21 to see the flag.

We could also reverse engineer the parts between “jmp loc_A3A” and the var_21 line to see how it gets the flag from the big arrays and then write code for that using Python or anything else.

While this was what I originally did, it turned out to be way too much effort for a really easy challenge.

BigArray[0] = "AFLdfgArTkdwelkfkmkasFFEWSWasCFsfsdfewRRWDSCFAWDHg";

BigArray[1] = "sddgrlksjpothjafkgpOEWFKQW0EOG9AWRI90VA8RUGWE9R8BIhDJFOIBSDF";

BigArray[2] = "SDSL;FKOKEIER0T9W85690843GJDKVJASFQLIGUQWO;ECLDskvjar;lgksjg1dflb";

BigArray[3] = "kjhKKHJLKlkjhlksriufer9erudskjhLKHJW3EROIWUEOIUkjkhsdllkejgrgpdffSljk";

BigArray[4] = "sdrdgkj4598fgjkksdffvggvljkt66yhpooijjKJWEROJISDOVIHEERGNoqiqwjedqwkd_jaasfefn";

BigArray[5] = "wewro3k34j4r39vjwewlkrfjwefoiasjALDLADSLFKWJEFWk23eqwqfweoryirut0h9dfbjlkwelkw1kj3e3f";

BigArray[6] = "xdlkjefwi9eru8239r2efjkldsvjlwk4g439berflklkjwff1982eiuqukKJSDFKJWEEF0OSDVJLKSKSLKJEFSJW0";

BigArray[7] = "098765432QWERTYUIOPASDFGHJKLZXCVBNM,W453948573498EWIFUERRGKHJFGBKDJGNBDDGksljgerogijdflkb_ckdfbj";

BigArray[8] = "dflfkgdjflgkjdflgsktjhworepgqajrlvLKLSADDKGJWREOGSJIFDLBKXDFGJBLKEKRTHHJOPSFGBJLSKFDGBJSLsdlfkdf4ldkfgj";

BigArray[9] = "DSLDFKGJWREGPOIWERJBSDFLKJBDFGLBKJklsdjff3948tueg98idduvvoierrguj0eer9gjgodfbbojiereoigsdfkgjdfdfdfdfdfNdb";

BigArray[10] = "dglkjerge9r0gwe9fwfoiuiSKDFJFWER9GDEORIJGDFOIBJRTOIBJDFOBIKJER90GGU3U3EGF09USEDGOISDFJGDOetewrtwertwfwFIJB_DF";

'''

.

. Cut for brevity

.

'''

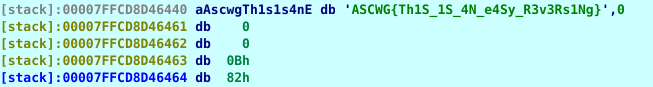

BigArray[25] = "flag dfsd dsf sdf "

flag = ['A', 'S', 'C', 'W', 'G', '{']

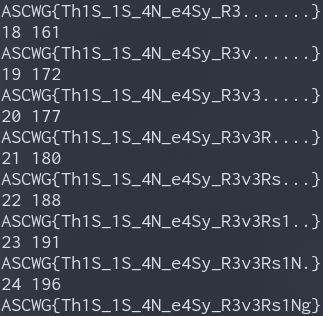

for i in range(50):

flag.append('.')

inputLength=6

indexing = 0;

while inputLength < 0x1f:

if indexing == 0:

flag[inputLength] = BigArray[0][8];

else:

strlen = len(BigArray[indexing-1])

print(str(indexing) + " " + str(strlen))

flag[inputLength] = BigArray[indexing][strlen];

inputLength = inputLength + 1

indexing = indexing + 1

for a in flag[0:31]:

print(a, end='')

print("}")

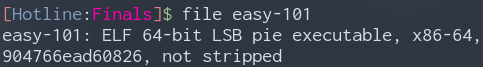

This gets us the same output:

Flag: ASCWG{Th1S_1S_4N_e4Sy_R3v3Rs1Ng}

Challenge 3 - mov

Challenge Difficulty: Medium

Challenge Link: Drive

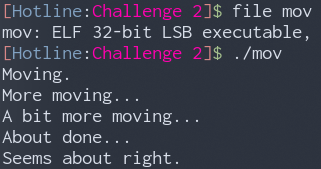

We are presented with a Linux 32-bit executable called mov. Running it doesn’t say anything useful except that it is “moving” something.

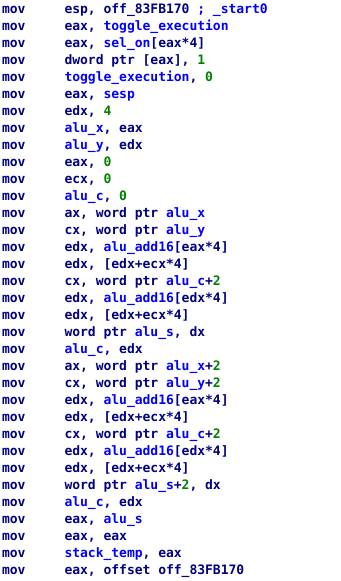

Opening the program in IDA, intuitively shows us that it consists of mov instructions only. That would be hell to debug.

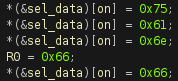

If we look around the binary we can see a lot of values in the ASCII range being moved into R0.

We can also open it in Ghidra’s decompiler and see something very similar but easier to understand.

If we extract all these values in order, we get the following string.

uanfsf_SConoAmibv}iW_s{uct_o!G

Knowing that out flag format is ASCWG{} and that usually in CTF flags words are separated by _ or -, we can reorder the character to end up with the flag

Flag: ASCWG{mov_obfuscation_is_fun!}

Challenge 4 - Hydra 1: KeyValidate

Challenge Difficulty: Hard

Challenge Link: Drive

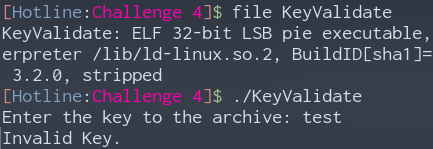

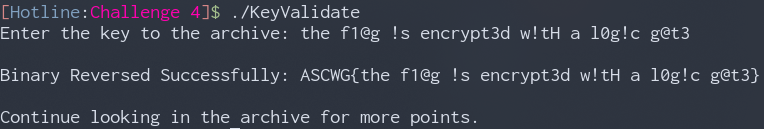

We are presented with a Linux 32-bit stripped executable called KeyValidate. Running it asks for a key.

Opening it in IDA, we can see that it uses MD5, this could be useful later on.

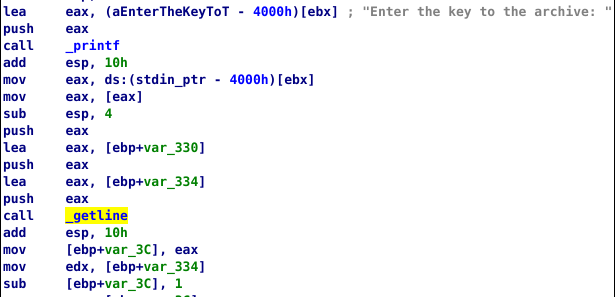

Checking the main function, we find that it takes they key using getline() after the prompt.

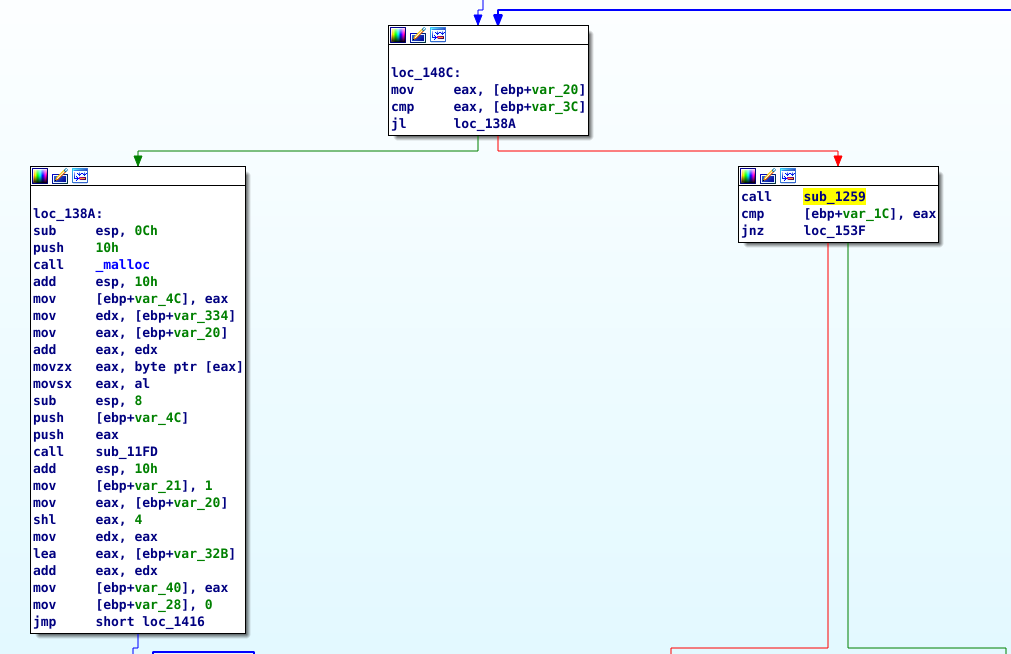

After that it gets into the validation loop.

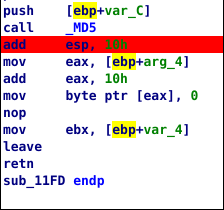

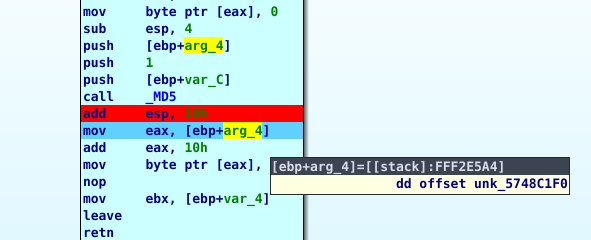

We can check for references to MD5() and we find that it is called inside Sub_11FD. This may be an indicator that MD5 is used for validation. We can run it with input “1234” and set a breakpoint right after the MD5 call to see what is being hashed.

We can see that the produced hash in arg_4 is the hash for “1” which is the first character of our input.

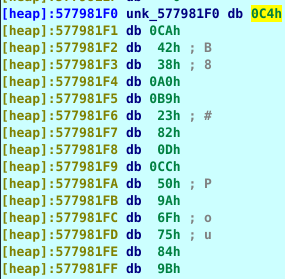

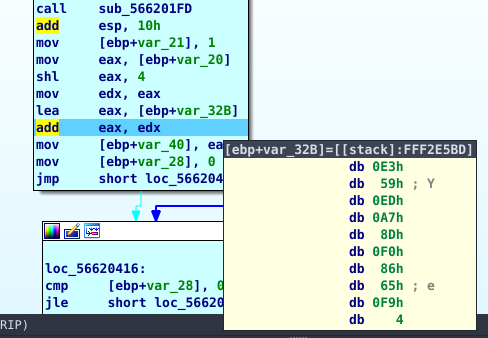

After the return from that function we can see that a huge array of bytes is being loaded into a variable.

After that, it compares the bytes of our inputs after they have been hashed, byte by byte compared to the required hashes stored in the binary. If it meets a wrong byte it returns.

The hashes stored in the binary are not the actual hashes, each byte has been XORd with its index ANDed with 0xFF. We can conclude this by checking the code for the validation.

XORdHashes[i] = Hashes[i] ^ ((i&0xFF))

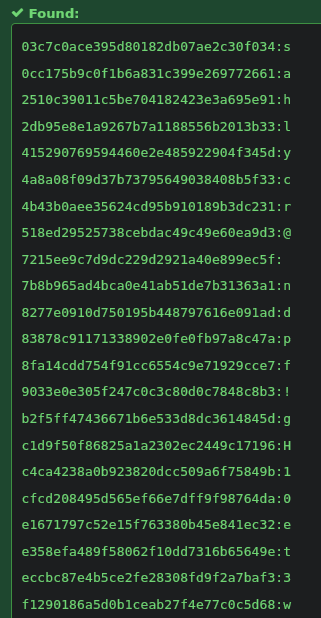

We can take that large array and do the exact process again (the perks of XOR) to get the original hashes and then break them on hashes.com.

hashes = [0xe3, 0x59, 0xed, 0xa7, 0x8d, 0xf0, 0x86, 0x65, 0xf9, ........]

for a in range(len(hahes)):

if a%16 == 0:

print("")

print(str('{:02x}'.format(hashes[a]^(a&0xFF))), end='')

After replacing each corresponding hash with its character, we get the string: the f1@g !s encrypt3d w!tH a l0g!c g@t3.

Plugging this into KeyValidate, we get the final flag.

Flag: ASCWG{the f1@g !s encrypt3d w!tH a l0g!c g@t3}

This challenge was joint with the challenge Hydra 2 which is a Forensics challenge written by 0x01g33k. Here’s a link to his writeup on the forensics challenges.

I hope you all enjoyed these challenges as much as I enjoyed writing them. See you in the next CTF!